by Raffaella Milandri

Since the development of nuclear power in the mid-20th century, Native American reservations have been subjected to thousands of tons of toxic nuclear waste, with dangerous consequences for health, the environment and tribal sovereignty. The disproportionate concentration of nuclear waste on Native lands is no coincidence. On the contrary, it reflects a targeted effort by the US government to impose ‘the most dangerous material ever created by mankind or nature’ on indigenous communities.

Native Americans and Canadians are peoples who have always lived symbiotically and with respect for Nature, for thousands of years. What worse disaster could there be than polluting and dumping nuclear waste in their reserves or opening uranium mines? I have attended meetings of Native activists in the United States on the subject, and it is not only about saving the environment, but also saving people: monitoring radioactivity and groundwater is one of the priorities of Native Americans. And not only that: also stopping new mines, as is happening in Lakota land in South Dakota. In this article I want to tell you in brief about yet another nefariousness.

The nuclear waste negotiator: radioactive racism

Said Keith Lewis, of the Serpent River Indian reservation in Ontario, Canada: ‘There is no morality in tempting a starving man with money. His tribe has been working in the uranium mines for over fifty years and lives near 145.3 million tons of radioactive waste, 75% of a total of 193.2 in the whole of Canada (Source: Gordon Edwards and Robert Del Tredici, Nuclear Map of Canada). The problem of nuclear waste even in the United States has not been solved: to this day it is still deposited near the more than 120 processing sites. Scientific American writes in an article on 6 March 2023: ‘A solution is needed before 35 US states become unsafe’.

Many attempts to ‘dispose’ of nuclear waste have been made at the expense of India’s poorest reserves Let us take a step back. In August 1990, President Bush appointed a ‘nuclear waste negotiator’, David Leroy, following the 1987 Monitored Retrievable Storage (MRS) project. Leroy had the menial task of contacting states, counties and Indian reservations with the aim of finding sites for ‘temporary’ dumps of highly radioactive waste, offering a rich financial benefit to those who accepted: he could give millions of dollars. Negotiator Leroy sent thousands of letters in 1991, but to no avail, treated almost like a pest; however, sixty Indian reserves responded and it seemed that things were looking good for his goal. Seventeen reservations approved ‘phase 1’: a preliminary phase of technical study paid for with $100,000, which appealed to the tribal councils of the reservations, whose accounts were always in the red. In 1992, several reserves wisely withdrew from the project and, at great effort, the negotiator managed to recruit nine of them for ‘phase 2A’, which would pay a contribution of $200,000 to carry out more in-depth investigations and studies. The Indian reservations were now the only target in the negotiator’s sights, lured by a substantial dollar bait: everyone else in the United States avoided the subject of radioactive waste.

In 1993, Bill Clinton appointed a new negotiator, Richard Stallings. In 1993, only four of the poorest tribes confirmed their interest in the landfill proposal: the Mescalero Apache, the Skull Valley Goshutes, the Tonkawa, and the Fort McDermitt Tribe; in October of that year, Congress voted to eliminate the project and the Negotiator, with a lapse in December 1994. But in December 1993, a private consortium of 33 nuclear utilities, led by Northern States Power, of Minnesota, decided to take over the Negotiator’s negotiations. The waste was ‘pressing’. By the end of 1994, only the Mescalero Apache tribe, one of the poorest in the United States, remained in negotiations with the consortium, which allegedly lavished considerable sums of money on the tribal council leaders. The tribal members, however, still remained in the dark after three years: no public meeting had yet been held on the reservation to discuss nuclear waste. In January 1995, the Mescalero people put the dump to a vote, and the project was rejected. Silas Cochise, Mescalero manager of the project, said: ‘It is our elders who do not want to risk the future of their grandchildren’.

In March 1995, tribal leaders on the Mescalero reservation called for a second referendum: rumours were circulating that if the referendum passed, each tribal member would receive USD 2,000; many also feared reprisals from the tribal council. The petition to hold the second referendum passed, although the signature collection sheets were never shown in public. And ‘finally’ the landfill was approved at the referendum. Ironically, immediately after the Mescalero approval, the consortium lost half of its member companies. It is an endless story of pressure, blackmail, corruption, deceit and double-dealing. In 1996, the Mescaleros broke off negotiations with the consortium led by Northern States Power (Source: Nuclear Information and Resource Service, http://www.nirs.com).

After the Mescaleros, in 1996 the consortium’s attentions focused on the tiny Skull Valley reservation of the Goshutes Indians, who were already in negotiations with the first negotiator. Skull Valley had become famous in 1968 when, following a military experiment with nerve gas, 6400 sheep ‘accidentally’ died there, whose toxic carcasses were buried on the reservation without asking permission from the Indians (Dugway Sheep Kill incident). The story went on until 2000, when a new consortium offered 60 to 200 million dollars to the small tribe. But by then the protests and environmental movements of the Native Americans had taken hold: this dump also did not happen. The radioactivity is called by the Indians ‘the smallpox-infected blanket of the Nuclear Age’.

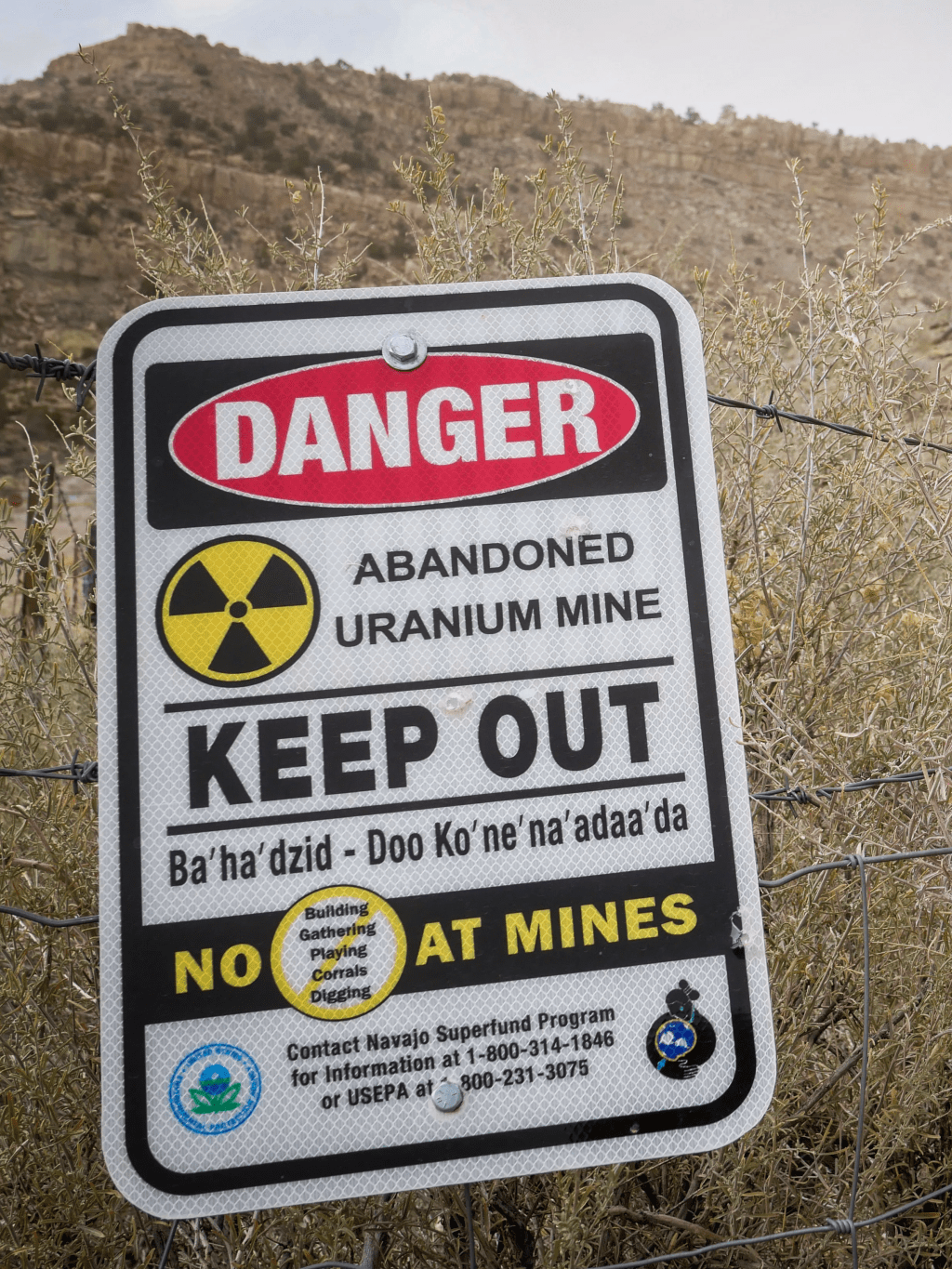

The Navajo Nation: over 500 abandoned uranium mines

Over 500 abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation, the largest Indian reservation in the United States, have poisoned the residents’ drinking water and caused high rates of kidney failure and lung disease for generations. Members of the Yakama Nation in southeast Washington, where the Hanford nuclear site is located, suffer from high rates of thyroid cancer and congenital disabilities. And the Western Shoshone tribe, which has been exposed to significant nuclear fallout from decades of nuclear testing on its territory (known as ‘the most bombed nation on the planet’), suffers from disproportionate rates of leukaemia and heart disease. Other examples of environmental contamination caused by nuclear waste radioactive material and other hazardous chemicals have been dumped into Washington’s Columbia River for decades, contaminating the Chinook salmon, which the Yakama Nation tribe has historically relied on as a primary source of food; in the Navajo Nation, radioactive material has been used to build homes and schools; in the Ute Mountain Ute tribe’s territory, near a working uranium factory in the United States, groundwater has been found to be contaminated with high levels of acidity and hazardous chemicals such as chloroform. These are just a few examples of the devastating health impacts caused by what activists and scholars have rightly described as ‘radioactive colonialism’.

For more data on uranium mining and production in the USA: https://www.eia.gov/uranium/production/annual/

The disproportionate amount of nuclear waste on Native land can be attributed primarily to the numerous legal, economic and regulatory power imbalances between Native American tribes and the US federal government. The federal government has intentionally identified and targeted reservations as potential repositories of high-level nuclear waste.

As a result of legal and political decisions limiting tribal sovereignty, health and safety standards on Native reservations are less restrictive than on non-native lands, as we have already seen in my article ‘The Truth about Indian Reservations’ (link: https://www.lantidiplomatico.it/dettnews-la_verit_sulle_riserve_indiane_le_terre_non_appartengono_ai_nativi_americani/53237_53818/ )

Lands do not belong to Native Americans. This is especially important when it comes to the nuclear industry. Years of nuclear testing and development on tribal land (as well as several resulting accidents) have led to great radioactive exposure and few consequences for those responsible.

David Leroy himself, negotiator for nuclear waste from 1990 to 1993, claimed: ‘Because of Indians’ great care and respect for Nature’s resources, Indians are the most logical people to deal with nuclear waste’. Ironic, isn’t it?

Nuclear dumps on Native land can be seen as a continuation of the long history of US exploitation and dispossession of Natives.

The government strategy (later adopted by private companies) has been widely criticised for capitalising and exploiting economically disadvantaged Native American communities with the highest poverty rate of all racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Financial incentives for storing nuclear waste on Native land have been described as ‘a form of economic racism akin to corruption’.

Resisting nuclear dumps

Nuclear dumps on Native land have been met with intense resistance for as long as they have occurred. There are several ways in which Native leaders have tried to fight back and seek justice. For example, they supported the expansion and renewal of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, a federal law that provides compensation to workers harmed by nuclear exposure.

Tribes, sometimes supported by states, have also filed lawsuits against the government and private companies for environmental and health risks caused by nuclear waste. These lawsuits have faced many procedural hurdles and some have been dismissed. Others, however, have resulted in favourable settlements, although no amount of money can fully repair the damage inflicted by nuclear waste. Other advocacy efforts include pressuring the government to clean up nuclear waste sites and calling for more research into the health impacts of nuclear waste.

Advocates have described nuclear waste on Native American reservations as a textbook example of environmental injustice: the disproportionate exposure of marginalised communities to environmental damage.

‘Oppenheimer’ doesn’t tell it right

Hollywood is thrilled with the $80.5 million blockbuster that Oppenheimer grossed during its opening weekend, as reported by Variety. Based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book American Prometheus, the film is about the so-called ‘father of the atomic bomb’.

But the President of the Navajo Nation, Bu Nygren, thinks that Hollywood has fallen far short of telling the story of the devastation that uranium mining and nuclear testing have caused to the country’s largest Indian reservation. ‘The Navajo people cannot afford to be, once again, erased from history,’ Nygren wrote in an editorial in TIME magazine on 21 July 2023. Nygren adds that the film was released five days after the 44th anniversary of the Church Rock uranium factory spill, when 94 million litres of radioactive waste poured into the Puerco River, which runs through the northern portions of New Mexico and Arizona, where the Navajo Nation is located.

‘What happened next – cancers, miscarriages and mysterious illnesses – is a direct consequence of America’s race for nuclear hegemony. It is an outcome built on the bodies of Navajo men, women and children, the lived experience of the development of nuclear weapons in the United States. But, as usual, Hollywood chose to gloss over them’.

Nygren concludes: ‘The Navajo people have suffered and sacrificed much, contributing directly to our country’s post-war quest for nuclear superiority. And while our Navajo Code Talkers are esteemed for heroically saving countless lives in the South Pacific during World War II, our uranium miners have been largely overlooked. The only thanks for their years of patriotic service has been death, illness and decades of battling for recognition of their sacrifice. The legacy of uranium mining on the Navajo is a perpetual stain on our nation’s history with its Native peoples, and the disregard of our stories by the media and films like Oppenheimer cannot mean continued erasure in US policy.’

Published originally in Italian in The AntiDiplomatico, 18 June 2024

Native column by Raffaella Milandri

https://www.lantidiplomatico.it/news-nativi/53237/

Articles by Raffaella Milandri

- Revenge of the Native Americans? Killers of the Flower Moon and Lily Gladstone

- What lies behind Pope Francis’ apology to Native Americans, exploring the historical context and significance of his statement in relation to Indigenous rights and healing

- The truth about Indian reservations. The lands do not belong to the Native Americans

- Forgetting the Native American Genocide: over 55 million dead

- Forced sterilisation: the latest weapon against Native Americans

- Leonard Peltier: the appeal for the Native American activist after 47 years of maximum security imprisonment

- Sioux-Lakota ban Governor Kristi Noem from entering Indian reservations

- Indian reservations inspired Nazi concentration camps

- Nuclear tests and toxic waste on Indian reservations. The film ‘Oppenheimer’ doesn’t tell it right

- Secret medical experiments on Native people in Canada: a lawsuit to prove it still happens today

- The ‘Manifest Destiny’ of the United States, Native Americans and the Rest of the World

- How do Native Americans see the situation in Gaza: a parallel path?

- Native American voting discrimination in US elections

- The paradox of Puerto Rico: American citizens but without the right to vote

- Native Americans and firewater (and Tim Sheehy’s statements)

- Alarm over Canadian police violence towards Native people: nine dead in the last month alone

- Canada tried – and still insists – on erasing Native rights

- Biden apologises to Native Americans: the (negative) comments and the background

Lascia un commento